Author Vikki Tobak chatted with Senior Editor Ashley Davis about iconic jewelry tropes and what they say about hip-hop’s place in society.

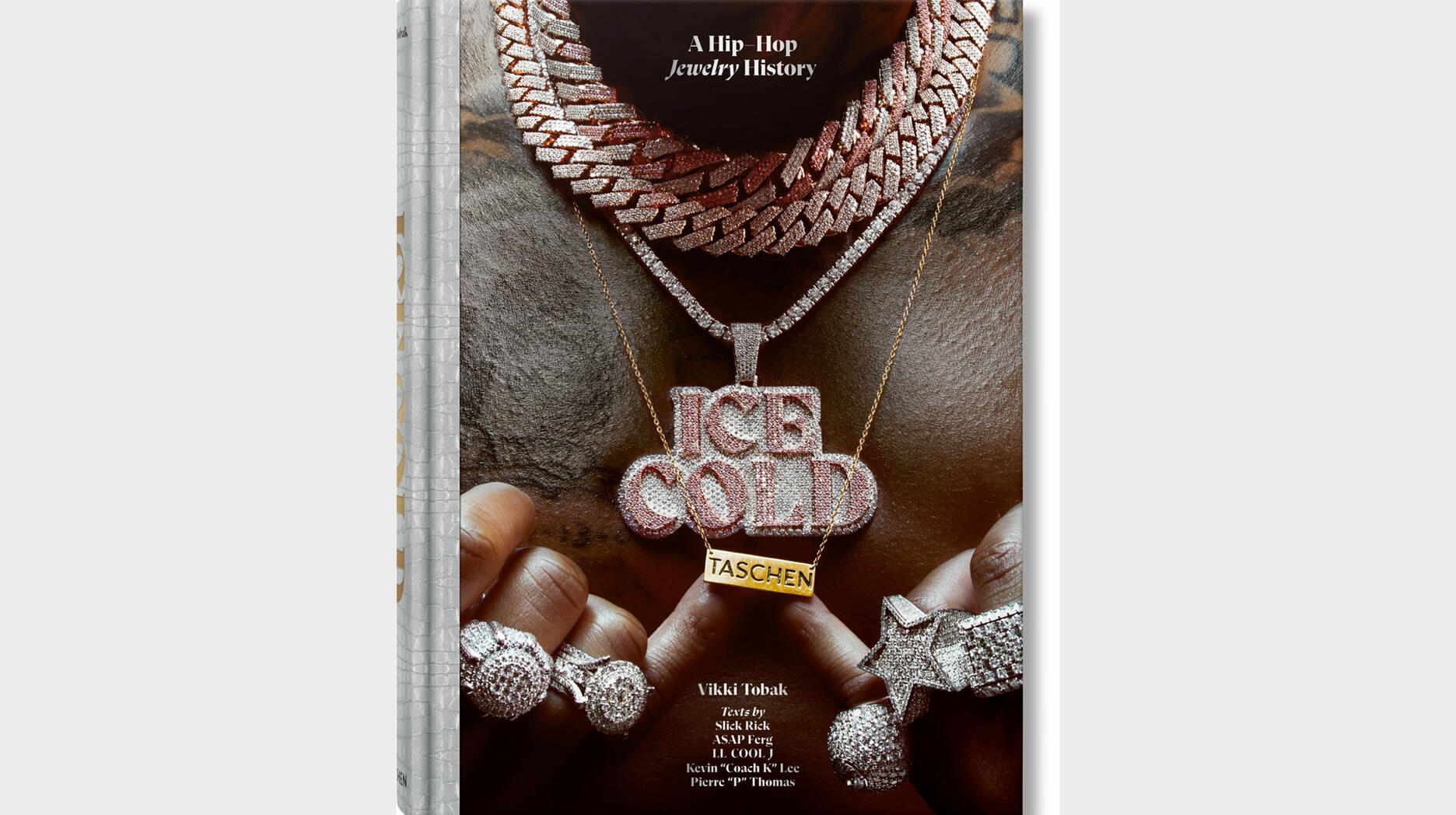

Published by Taschen and written by Vikki Tobak, “Ice Cold. A Hip-Hop Jewelry History” is available at booksellers now.

I’ve found the perfect holiday gift for jewelry lovers.

New release “Ice Cold. A Hip-Hop Jewelry History,” by Vikki Tobak is a sumptuous addition to one’s jewelry book library, rich in both imagery and text.

Tobak is a longtime hip-hop journalist. “Ice Cold” couldn’t exist without her first book, “Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop.” In that, Tobak explored hip-hop through the lens of contact sheets from film photography, supplementing them with interviews with artists and photographers.

In “Ice Cold,” she narrows her focus, honing in on jewelry’s role in hip-hop, how it has changed and remained the same over the art form’s short history, and what it says about hip-hop’s place in society today.

Tobak began researching “Ice Cold” in earnest in 2020, her plans of interviewing jewelers in the Diamond District and throughout New York City’s boroughs supplanted by internet research rabbit holes and Zoom calls.

Two years later, her journey has culminated in easily the most exciting jewelry book of the year, in which she plays not only journalist and curator, but also anthropologist.

Published by Taschen, “Ice Cold” features a foreword from rapper and record producer Slick Rick and essays by A$AP Ferg and LL Cool J, among others.

I spoke with Tobak about her creative process in crafting “Ice Cold,” iconic jewelry styles in hip-hop like nameplate necklaces, and the greater cultural implications of hip-hop’s synergy with the luxury market.

National Jeweler: How did you come to write a book on jewelry’s role in hip-hop?

Vikki Tobak: I’ve been a writer and journalist covering hip-hop since the early ‘90s. Before that I started out working in the music business for a small record label called Payday, so I’ve known a lot of the artists and the community and the culture since the early ‘90s.

In 2018 I did a book called Contact, which was a photographic history of hip-hop. As I was dissecting all those photos, I couldn’t help but notice all the little visual details in there from the sneakers to the fashion and that included the jewelry.

Slick Rick. Libra justice scale piece, diamond star and dome rings from various years purchased mostly from jewelers on Canal Street, New York City. (Credit: Clay Patrick McBride, New York, 1999)

I got really interested in jewelry as identity and the different jewelry styles that developed in hip-hop. Jewelry has just been such a big part of it from the start.

NJ: When it came to the process of pulling together this book, what was that like for you? There’s such a huge amount of jewelry; where did you even start? And what was the curation process like?

VT: A few ways. I started with just understanding the story of hip-hop and who influenced the street culture that really influenced hip-hop before there were even well-known artists. And then looking at those early days and into today at who was known for their jewelry, like people like Slick Rick, who wrote the foreword.

Through them I researched jewelers and a lot would name check jewelers in their songs. So you had Tito Caicedo who had a shop called Manny’s and then came Jacob the Jeweler.

If you follow the string of the early artists in the culture you’re led to the jewelers and the sort of places and spaces where all that happened.

Jacob “The Jeweler” Arabo of Jacob & Co. Jacob “The Jeweler,” seen here in his Diamond District shop, became the premier jeweler as hip-hop stepped into its power in the 1990s. Name checked in scores of hip-hop lyrics, he helped usher in the era of platinum and diamonds for the culture. (Credit: Jamel Shabazz, New York, 1990s)

That was one path of research. Another was making sure that the photographs were there to support the story. I leaned into my community of photographers whom I’ve known and worked with for many years and also collaborated with on my first book.

Lastly, I looked into the styles themselves: the link styles like the Cuban links, the four-finger rings, the door knocker earrings, the grills, which are like a subculture within the subculture. It was just like a Venn diagram of all those points that informed the curation process.

The same way I looked at rappers Biz Markie and Slick Rick in the beginning of hip-hop, I also looked to current artists like Tyler the Creator and Gucci Mane and Pharrell in the same way.

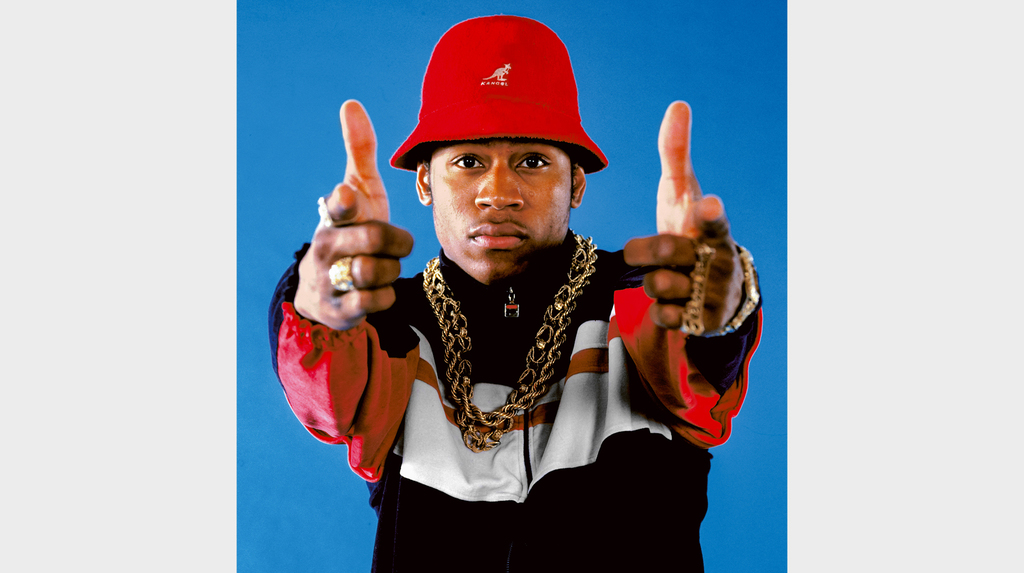

LL Cool J. LL Cool J is one of the most influential rappers when it comes to hip-hop jewelry, wearing four-finger rings and dookie chains alongside some of the most iconic stylings in hip-hop history. Nameplate ring spelling “James,” his first name, double-layered gold rope chains, and Gruen gold nugget watch. (Credit: Janette Beckman, New York, 1988)

NJ: I like what you say about the Venn diagram. I think that’s a fitting way to describe jewelry now versus jewelry then with so many styles kind of overlapping. Are there certain styles that really stood out to you as being the stars of hip-hop jewelry?

VT: Yeah, chains like the Cuban link are a classic, the “Jesus Piece” that’s been sort of riffed on many times in many different ways.

Even Gucci links and mariner links. Though they are considered pretty classic, in hip-hop they have been sort of remixed and rethought of because hip-hop is rooted in a culture of remixing, not just for music but for everything including clothing. It’s all about remixing, reinventing and customizing. You see that in things like sneaker culture.

You don’t want anything that someone else has. That’s also a big part of the culture and has really informed jewelry styles, and why some are so over the top and unique and so personal.

NJ: I’m curious about the nameplates that are featured a lot in “Ice Cold.” Subjectively, from all your research, what do you think makes a great custom nameplate?

VT: Something that really speaks to someone’s identity and is personal. Early on, nameplate belts were a big, big thing. Nameplates have been like a rite of passage. They have been something that a young girl would get if she turned 16 for example.

I think what really just makes a good one is if it’s personal and it’s connected to a special moment. So much of jewelry is like that.

Megan Thee Stallion. “Hot Girl” moniker pendant and baguette diamonds on a custom diamond-encrusted flames link made with 155 carats, approximately one kilo of 14-karat gold, and VS diamonds by Eliantte & Co. (Credit: Marcelo Cantu, Los Angeles, 2020)

Now there are these giant nameplates that are made of diamonds and way oversized and large and that is fun, too. You could almost say nameplate culture is a subculture within the culture of hip-hop jewelry. I think the most important thing is that it’s tied to something really personal.

NJ: Nameplate almost doesn’t seem like a large enough word to encompass the range of name pendants that exist.

VT: It does seem sort of limiting to just call it that because it goes so much deeper. A lot of times those were made by your local jeweler so that made it even more sort of community-based and a rite of passage.

Each hip-hop community—whether in Brooklyn, Queens, or Los Angeles—would have their own specific local jewelers so that too really ties it to people’s identities and where they’re from.

NJ: Do you have any favorite pieces that stand out from the book? Are there any jewels that particularly resonate from your whole experience of making Ice Cold?

VT: There are and for different reasons. I really like the Biggie Jesus piece. I call that like the Hope Diamond of hip-hop jewelry because it really set the trend of rappers wearing Jesus pieces.

Notorious B.I.G., a.k.a Biggie Smalls. Created by Tito Caicedo of Manny’s New York, Biggie’s Jesus piece set off a trend in hip-hop that is now a staple look for artists. In Jay-Z’s book “Decoded,” he explained how Biggie’s pendant became iconic in hip-hop and a good luck symbol for him (Jay-Z): “The chain was a Jesus piece—the Jesus piece that Biggie used to wear, in fact. It’s part of my ritual when I record an album: I wear the Jesus piece and let my hair grow till I’m done.” The “Jesus piece” is also referenced in the song “Hypnotize,” one of The Notorious B.I.G.’s biggest hits: “So I just speak my piece, keep my peace/Cubans with the Jesus piece, with my peeps...”—The Notorious B.I.G., “Hypnotize” (Credit: Michael Lavine, Queens, New York, 1997)

After Biggie passed Jay-Z would wear it when he would record. The style has been reinvented so much. Kanye commissioned a Black Jesus and then a Murakami Jesus.

As iconography the Biggie Jesus Piece has lived on and been remixed in hip-hop culture. It was made by Tito Caicedo so it has a special place in my heart because it’s by an important jeweler and worn by an icon of hip-hop.

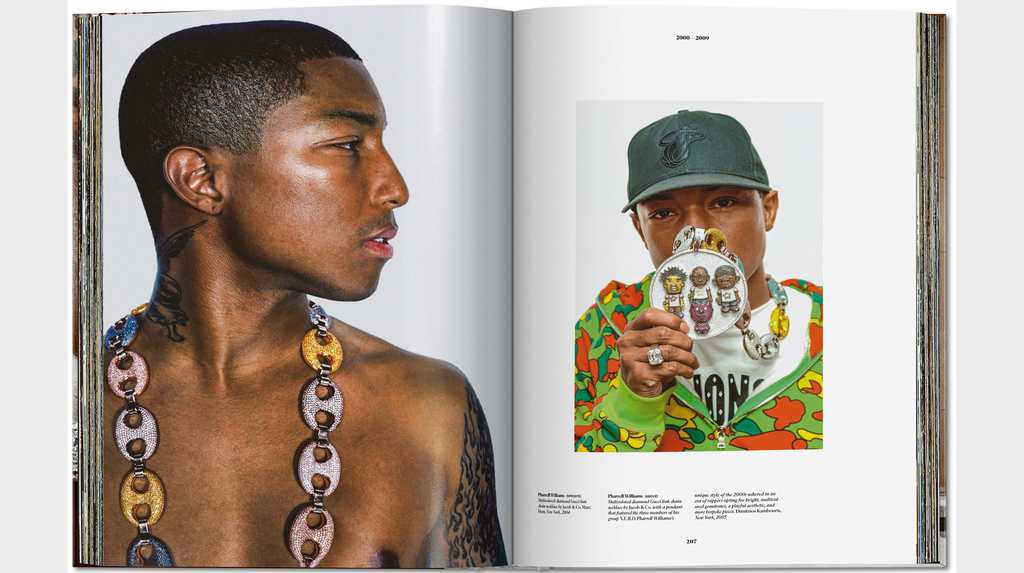

In terms of a piece that I would want to own, I love the Pharrell puffy Gucci link that Jacob & Co. made, which was auctioned on Pharrell’s new auction platform. The piece is stunning in person. Pharrell really ushered in the use of multicolor stones and more playfulness and really opened the door to the next generation of hip-hop collectors who are commissioning all these really interesting, different looks.

I also love seeing all the women in hip-hop starting to collect. Hip-hop has had a very male-dominated collector base but now you see Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion and Latto who are commissioning these fun, great pieces. I've just been loving seeing that because it’s so empowering.

NJ: I love seeing social media posts and reading articles about hip-hop stars and their kids’ jewelry too. Cardi B has had some amazing pieces created for her daughter Kulture.

VT: In the last pages of Ice Cold we have a spread that shows a bracelet with enamel teddy bears that was made for Kulture. This connection jewelry has to concepts of building generational wealth and creating a legacy for your family [is an important part of jewelry in hip-hop], just as you see with what Cardi and (partner and Migos rapper0 Offset are doing for their daughter.

I talked to Coach K and P from (record label and music-and-sports management company) Quality Control, who are both big watch collectors. They talk about how their watches are going to be passed on to their children and it’s sort of reflective of hip-hop really stepping into its power with people building labels and becoming entrepreneurs and exerting this spending power that is very meaningful. Jewelry is really part of that, too.

Pharrell in the recently auctioned Jacob & Co. puffy Gucci link necklace. (Image courtesy of Taschen)

NJ: Your book really goes beyond jewelry as adornment. Like you keep saying there’s so much more significance to its place in hip-hop than just the designs.

VT: That’s why it’s really interesting to observe this moment in time because of the way that hip-hop in general is interacting with the luxury market.

Tiffany has embraced hip-hop culture by having A$AP Ferg as their first ambassador from the hip-hop world and then having Jay-Z and Beyoncé star in their advertising. Even if you look at their “Hardware” collection, it’s very informed by these chunkier link styles and almost straight out of hip-hop culture.

It’s interesting to think about it in the context that 20 years ago this world of luxury wanted nothing to do with hip-hop and actively tried to not have people wearing their stuff.

Today, people like A$AP Rocky and other hip-hop stars are front row at fashion shows. It has come so far and it’s a really important and interesting time in history to sit back and observe it.